Metacognition

“Metacognition is, simply put, thinking about one’s thinking” (Chick, 2013) and is a core competency that all students should acquire to assist them with understanding how they learn, what is working, and what may need to change.

“Metacognition is, simply put, thinking about one’s thinking” (Chick, 2013) and is a core competency that all students should acquire to assist them with understanding how they learn, what is working, and what may need to change.

When students demonstrate poor metacognition, they are unaware of their strengths and challenges in learning and have limited knowledge or ability to know how to improve in this area. Alternately, those students who demonstrate good metacognition are aware of their challenges in learning but the difference here is that they know what they need to do to improve. This self-awareness is key to success in post-secondary education. Take a look at this video which explains the different components related to metacognition for learning.

Learners who enter post-secondary education are often unaware of what learning entails, and how to improve on existing strategies. Evidence shows that if the correct strategies for learning are applied and learners apply metacognition, their chances of success are greatly improved. Two key processes are essential for metacognitive learning.

Knowledge of Cognition

Knowledge of Cognition

- Awareness of factors that influence your own learning

- Knowing a collection of strategies to use for learning

- Choosing the appropriate strategy for the specific learning situation

- Regulation of Cognition

- Setting goals and planning

- Monitoring and controlling learning

- Evaluating own regulation (assessing/reflecting if the strategy is working or not, adjusting, and trying something new)

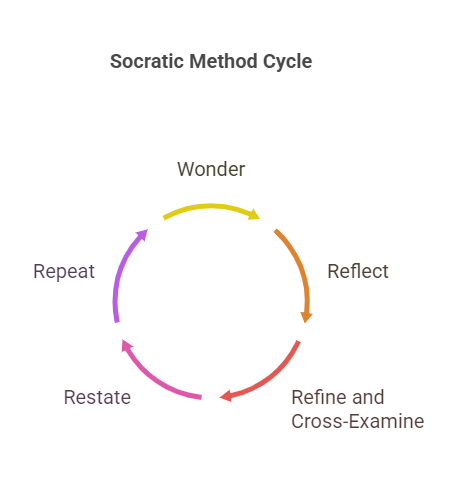

The diagram to the right depicts the metacognitive cycle developed through the process of knowledge and regulation of cognition. The arrows remind us that metacognitive thinking is a reflective process and requires the learner to constantly scrutinize what is working, what is not, and actions to take.

| Be intentional about teaching metacognitive skills. When designing your course, identify opportunities in which to incorporate strategies to teach metacognitive skills. For example, you might decide to build metacognitive strategies into an assignment, or around your midterms. Decide when to focus on self-regulation skills and when to focus on guiding learners to think metacognitively about course content. | |

| Be explicit when teaching metacognitive skills. Talk about metacognitive skills with your learners; define metacognition and explain why developing metacognitive skills is important during and after college. If you have structured your course so that specific themes, relationships or contrasting perspectives emerge, give learners your road map or use activities such as a concept map to help them identify it themselves. In other words, don’t assume that learners will automatically see relationships that might be obvious to you. | |

| Encourage goal setting. Prompt learners to consider why they are taking your course, what grade they want to earn and how they plan to achieve that goal. For example, have learners work in groups to brainstorm strategies for earning an “A” in the course. | |

| Develop ways for learners to “stop and take stock” during class. During class, ask learners to pause for 1–2 minutes and think about what they are doing at that moment (i.e., taking notes, engaging in off-task activities, working on another course). After the pause, this could be a good time for learners to ask questions. | |

| Prompt learners to think about how they prepare for class. At the beginning of class, show a slide with the prompt “How have I prepared for class today?” Ask them to write their answers to a set response option. Showing multiple response options enables learners to see strategies that they might not have thought of on their own. Talk about your expectations regarding class preparation and why that is important to their learning. | |

| Emphasize the importance of learning versus getting the correct answer. After posing a question to the class, give learners time to discuss how they arrived at the answer they chose. Specifically, ask them to consider their process, the main reason for choosing the response, why they discarded other possible steps or answers, how confident they were about their answer, etc. Follow up with an explanation of why you have asked them to spend time on this. | |

| Link the purpose of an assignment to course objectives and professional skills. When giving an assignment, ask students to think about why you chose that assignment and how it relates to their professional development. See Tables 1 and 2 in Tanner 2012 for prompts. |