Course Design

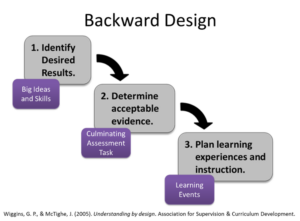

Course design/redesign is an ongoing and iterative process. In this section, we explore ‘backward design.’ Backward design is an educational framework that starts with identifying desired learning outcomes before planning instructional methods and assessments.

1. Start with the learning, not the content — First, clarify what students should meaningfully know or be able to do by the end of the course. Content serves the learning—not the other way around. This means designing learning outcomes. The previous section outlines learning outcomes: what they are, why they matter, and how to write them.

learning—not the other way around. This means designing learning outcomes. The previous section outlines learning outcomes: what they are, why they matter, and how to write them.

2. Focus on enduring understanding, not coverage — Ask yourself:

- What should students still understand months or years later?

- What ideas or skills transfer beyond this course?

- What knowledge, skills, and attributes do you want students to learn?

- How will the above be articulated in the course learning outcomes?

Prioritize depth over breadth.

3. Write learning outcomes in plain, observable language — Well-written outcomes:

- Use clear action verbs (e.g., analyze, design, justify)

- Are observable and assessable

- Reflect the level of thinking appropriate to the course (introductory → advanced)

4. Design assessments before activities — Before planning lectures or assignments, ask: What would count as convincing evidence that students achieved the outcome? Assessments should directly align with outcomes—not just be convenient to grade.

5. Use multiple forms of evidence — Avoid relying on a single high-stakes assessment to support diverse learners. Consider a mix of:

- Low-stakes practice

- Applied tasks

- Reflection

- Collaboration

6. Align activities with outcomes and assessments — Every major activity should clearly answer:

- How does this help students succeed on the assessment?

- Which learning outcome does this support?

If the connection isn’t obvious, students will struggle—and disengage.

7. Design learning experiences intentionally — Choose teaching strategies based on what students need to practice, not what feels familiar to teach.

Ask:

- What kind of thinking do students need to rehearse?

- Where do they typically struggle?

Active learning, guided practice, and feedback matter more than polished delivery.

8. Make expectations transparent — Backward design supports clarity. Sharing the following with students through the course outline supports equity and builds transparency and trust.

- Learning outcomes

- How assessments connect to those outcomes

- What “good work” looks like

9. Build in opportunities for feedback and revision — Learning improves when students can:

- Practice

- Receive feedback

- Try again

Design space for iteration, especially of complex or high-impact tasks.

10. Use backward design as a redesign tool, not just a planning tool — When revising an existing course:

- Identify outcomes that no longer fit

- Remove or simplify activities that don’t align

- Adjust assessments before adding new content

Backward design is often about letting go, not adding more.

11. Consider inclusion from the start — Backward design works best when paired with inclusive thinking:

- Are outcomes culturally responsive?

- Do assessments allow multiple ways to demonstrate learning?

- Are barriers anticipated and minimized?

12. Revisit and refine — Backward design is iterative. Each time we teach a course, we need to reflect on the experience, asking ourselves:

- What evidence showed real learning?

- Where did students struggle unexpectedly?

- What could align more clearly next time?

For more information, click on Foundations of Course Design